Telegraph Hill and North Beach (Part 2)

Telegraph Hill

After skirting the summit of Telegraph Hill on Day 1, I climbed to the peak on Day 2. And what a treat!

Filbert Steps (Up)

The east slope of Telegraph Hill is very steep. The best way to ascend Telegraph Hill from the east is via the Filbert Steps. Filbert Street becomes the Filbert Steps when even a sloped sidewalk would be too steep.

Coit Tower

Of course the main reason to get to Telegraph Hill’s summit is to get to Coit Tower. Coit Tower has some of the best views in the city. But as you’ll see, it’s also an amazing, historic, and free art gallery.

In the lobby of Coit Tower are dazzling Depression-era murals painted by various artists under the Public Works of Art Project in the 1930s under the New Deal. The Public Works of Art Project was a WPA for artists. Most of the artists were faculty and students at the California School of Fine Arts, precursor to the San Francisco Art Institute. Like much of the commissioned art of the era, the murals were somewhat controversial because the artists incorporated leftist themes into their work.

Greenwich Steps

When I was ready to descend Telegraph Hill, I took the Greenwich Steps, parallel to the Filbert Steps.

Filbert Steps (Down)

At Montgomery Street, instead of proceeding down the Greenwich Steps, I rejoined the Filbert Steps further south. I descended to the base of Telegraph Hill via the Filbert Steps.

Back to North Beach

Washington Square and Telegraph Hill are both in North Beach. But usually when I think of North Beach, I think of the very busy commercial district centered on Broadway and Columbus Avenue. In the morning, I had stopped by North Beach for a bite before setting off for Russian Hill. Now I was ready for the full tour of North Beach.

The Beat Museum

“I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked…”

My first stop on my tour of North Beach was the Beat Museum. In the ’50s, North Beach became Greenwich Village West as San Francisco drew members of the Beat Generation to North Beach’s bars and caffès. I expected the Beat Museum to be a junky site exploiting North Beach’s Beat Generation fame. But I was very impressed. I definitely recommend it to anyone interested in the American counterculture in the ’50s and ’60s. (And I personally can get obsessed with the ’60s.) The Beat Generation is mostly associated with the ’50s. But they really invented the ’60s as we know them.

John Lennon became fascinated by the Beats. That’s partly why he named the biggest band of the ’60s the Beatles instead of the Beetles. Bob Dylan was also infatuated with the Beats. He named his 1965 song “Subterranean Homesick Blues”–the one with the famous cue-card video–after Jack Kerouac’s book “The Subterraneans”. It was Dylan’s first Top 40 hit. And who’s lurking in the background of the famous cue-card video? None other than Allen Ginsberg. In the ’50s, the Beats were known for getting stoned on marijuana (among other substances). In the ’60s, they were on the forefront of the rise in the popularity of the recreational use of LSD.

To me, Neal is most famous as the inspiration for Dean Moriarty, the bad influence in Jack Kerouac’s defining work, 1957’s “On the Road”. But it seems that Neal had a distinct stream of consciousness speaking and letter-writing style. Jack emulated this style, as well as the rhythms of jazz, when writing “On the Road” in what he called “spontaneous prose”. This style also influenced Allen Ginsberg in the writing of his groundbreaking 1955 poem “Howl”.

Jack Kerouac himself originally applied the 1940s term “Beat Generation” to his circle of counterculture writers. “Beat” originally referred to a generation that was beaten down. Jack assigned an more positive connotation to the expression by attributing it with aspect of beatific, as well as the beat of jazz. After all, they were “angel-headed hipsters.”

“Beatnik” was a derogatory term first used in a column in the “San Francisco Chronicle” by journalist Herb Caen in 1958. Herb merged “Beat” with the “-nik” from Sputnik. Like Sputnik, the Beats were seen as a threat to America coming from the left in the late ’50s. Herb Caen also popularized the word “hippie” in 1967. It had been in use by San Francisco journalists since 1965 as a diminutive of “hipster” to refer to the countercultural successors to the beatniks, who had shifted their center of gravity from North Beach to Haight-Ashbury.

Writer Ken Kesey had had a big hit in 1962 with his novel “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest”. Also in the early ’60s, he had volunteered for what turned out to be secret, no-so-legal experiments near San Francisco by the CIA on the effects of LSD and other psychoactive drugs. Ken grew very fond of LSD and encouraged his friends to experiment at parties with LSD that he absconded with. Ken called the parties the “Acid Tests”.

By this point, Ken became friends with Neal Cassady, who was living with Allen Ginsberg in San Francisco at the time. In 1964, Ken had to meet his publishers in New York. Instead of flying, he decided to make a cross-country piece of performance art. Ken, Neal, and their circle of friends, known as the Merry Pranksters, took off for New York in a psychedelically painted bus named “Furthur”, getting high all the way. Tom Wolfe–who went on to define the ’80s with “The Bonfire of the Vanities”–novelized the acid-drenched adventure in his 1968 book “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test”. “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test” became the seminal document of the hippie movement. After the trip, Ken continued to throw his Acid Test parties throughout the Bay Area.

In the meantime, Neal introduced Ken to his friends Allen Ginberg and Jack Kerouac. And Allen introduced the lot of them to his new friend Timothy Leary. Tim had been experimenting with psychedelics at Harvard. Allen had heard about the experiments and became an eager participant. Together, the two of them set out to expand the best minds of their generation. Starting to see how this all comes together?

Jack Kerouac, Neal Cassady, and a bookstore owner to be named later were in the audience at the Six Gallery reading. Jack wrote about the night in his 1958 book “The Dharma Bums”.

The Human Be-In was a direct reaction to a 1966 law banning LSD in California. Tens of thousands showed up for the Human Be-In. A special batch of LSD was distributed. Timothy Leary encouraged the masses to tune in, turn on, drop out. Due to the publicity that the event received, young people from all around the country started streaming into San Francisco and Haight-Ashbury. The stage was set for 1967’s Summer of Love. (It’s stuff like this that makes me obsess about the ’60s and regret I was just a few years old at the time.)

And the Beat goes on…

North Beach Arts and Entertainment

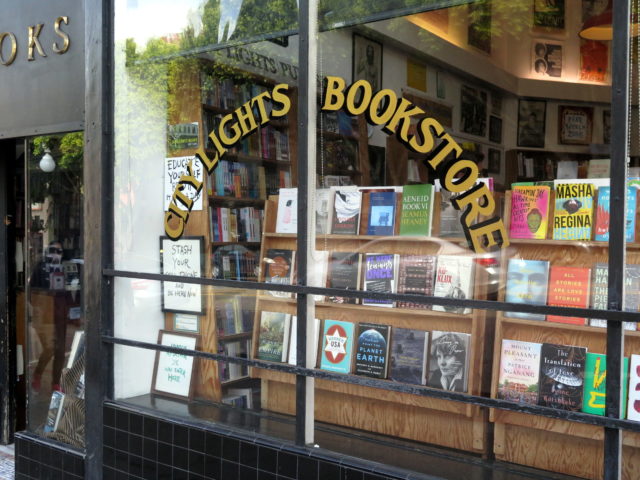

City Lights, named after the Charlie Chaplin movie, was co-founded in 1953 by poet and activist Lawrence Ferlinghetti as the country’s first all-paperback bookstore. In 1956, through City Lights Publishing, Lawrence published Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl and Other Poems”. (He is the bookstore owner referred to above as being present at the Six Gallery reading.) Lawrence and the store manager were arrested for publishing and selling obscenity. A sensationalized trial followed in 1957. The judge ruled that “Howl” had redeeming social importance. It was a huge win for the First Amendment and for the fame of City Lights.

City Lights Bookstore was a popular hangout for the Beat Generation. The Beats are gone, but on March 24, 2016, Lawrence Ferlinghetti turned 97.

Across an alley from Tosca and directly across Columbus Avenue from City Lights and Vesuvio is San Francisco’s weirdest: Specs’ Twelve Adler Museum Cafe. It’s a dark bar with lots of whacky stuff. It’s been a popular offbeat hangout since 1968.

In the evening, my friend Tommy joined me to take in a San Francisco institution, “Beach Blanket Babylon”. First presented in 1974, it’s the world’s longest-running musical revue. We both hated it. The talent of the performers was undeniable. The outrageously sized wigs and headdresses were impressive. But the writing was cringe-worthy. Many of the jokes were stale. And there was just zero internal logic to the whole thing. To me, it’s strictly for tourists. There are thousands of San Franciscans who would disagree with me.

They say the neon lights are bright on Broadway, and that includes San Francisco’s Broadway.

[Factual information is primarily gathered from Wikipedia, so you know it must be true.]

Leave a Reply